Clics Modernos: The Argentine invasion of Electric Lady Studios

When Charly García met Joe Blaney.

Patti Smith sent out some of her memories today via her Substack about Electric Lady studio - “the beautiful house that Jimi built” - which is celebrating its 55th anniversary this week.

I do not have personal stories of being in the studio - although my family lived just a few blocks away for a lot of years; as a high schooler, I’d just stare at the door as I walked by, hoping to catch some of the magic I imagined happening inside. But it seems like a good day to remember an album and an artist that had a big impact on me when I moved to Buenos Aires in 1986: Charly Garcia’s Clics Modernos.

One day in 1983, Argentine musicians Charly García and Pedro Aznar knocked on the door of Electric Lady on West Eighth Street in New York’s Greenwich Village. They were determined to make Garcia’s next album in Jimi Hendrix’s hallowed recording studio. The result, Clics Modernos, was a milestone album in South America both for its new wave sound (deemed the first Argentine release to feature a drum machine) and for boldly capturing the spirit of a country that was blinking its way from the darkness of a murderous dictatorship into the light of democracy to the beat of a thriving music scene.

In a 2015 interview for Billboard, engineer Joe Blaney told me about the day he met Garcia. Shortly before, he had passed a threshold in his career when he worked on The Clash’s Combat Rock:

“In 1983, Charly came to New York; he rented an apartment with an upright piano. He had a friend, Pedro Aznar, living here at the time, and they composed some songs. And then one day they came and knocked on the door of Electric Lady, the studio that I was affiliated with. That would have been in September of 1983. They said they wanted to make a record, the studio told them to go away, because back then, you just didn’t do it like that. And then a guy who was with them had a big wad of 100 dollar bills in his t-shirt pocket. He pulled it out and said to the owners of the studio something like, ‘You smell the money here?’ And they talked to him, and I made this record with them called Clics Modernos.

We came in every day and recorded like one song a day using a drum machine as a base. In the case of Clics Modernos, it was one of the first times I had used the drum machine. I didn’t really know what I was going for — I was trying to make it sound like real drums, processing it quite a bit.

He and Pedro had already worked out their parts, so they were just refining them. In the early ’80s, there were a lot of keyboard technologies coming out, and Charly was the kind of guy that if he got a certain sound on a keyboard, he would all of a sudden have a new part. There was a kind of fire in him; he would be creating up until the time when we finished the recording. There were always elements of improvising.

He left to go to Los Angeles and finish the record. And then I got a call a few days later that he wanted to mix it with me, and he came back to New York. I had gotten really busy by then, and we had to mix the whole thing in like four days. I knew we made a good record — I was very impressed by he and Pedro’s abilities and talent. But I had no idea this was going to be such a big record in Argentina.”

Blaney would after that go on to work on more than two dozen albums by Latin American artists. “…All of a sudden, the phone started ringing with everybody from down that way calling me,” he remembered. “Charly opened the doors to a career I never intended or designed.”

But when he worked with García on Clics Modernos he did not know much about Latin American politics – or South American rockers. He later recalled the emotion that permeated the studio during the recording of the synth-pop piano ballad “Los Dinosaurios,” when Argentine friends of the band who were there were moved to tears as García sang the lyrics:

Los amigos del barrio pueden desaparecer

Los cantores de radio pueden desaparecer

Los que están en los diarios pueden desaparecer

La persona que amas puede desaparecer…

Neighborhood friends can disappear,

The singers on the radio can disappear

The people in the newspaper can disappear

The person you love can disappear…

García occupies a particular place in the firmament of Argentine rock gods for his work in the 1970s and early 1980s when his songs presented a courageous chronicle of the times wrapped in metaphor.

During Argentina’s military dictatorship from 1976-1983, an estimated thirty thousand people, known collectively since then as the disappeared, were abducted during the years-long siege of State terrorism. In Buenos Aires, citizens were routinely detained; and they were tortured, and raped. Many were never accounted for, nor the circumstances of their deaths documented, but the testimonies of those who were detained and later released have given clues to the circumstances of the murders of those who were never found.

The majority of the victims were under 29 years old, according to government reports; the same demographic that was the target audience for new music in sync with a global youth revolution. In Argentina, however, it was a revolution that emerged against a horrific backdrop of national repression and violence.

“In Argentina there wasn’t an explicit situation of permanent war,” music journalist Marcelo Fernandez Bitar explained to me for a story that I wrote for No Depression. His 1987 book Historia de Rock en Argentina stands as a chronicle of the country’s early history of rock, but is also a revealing diary of an alternative music scene that persisted during the years of the military dictatorship, ultimately preparing the country for the cultural boom that followed in what Fernandez calls “the democratic Spring.”

“It wasn’t about tanks in the street,” Fernandez Bitar said during a phone conversation. “It was happening somewhat behind the back of mainstream society. At the same time, the dictatorship was being manipulative, sending a hypocritical message that they were the ones who were maintaining order and taking care of the people. So a big sector of society ignored or wanted to ignore, or looked the other way from the atrocities that were being committed.”

Clics Modernos, García’s second solo album, came out just a month before President Raul Alfonsín toook office, ushering in democracy in Argentina in December 1983. While the album is permeated with an ecstatic sound that’s unmistakably of the MTV era, it referenced the dark edges of the country’s reality.

“This is a song that everyone likes a lot,” the always provocative García said dryly as he introduced “Los Dinosaurios” during the taping of his 1995 MTV Unplugged, “Especially the dead people.”

In addition to “Los Dinosaurios,” whose bleaker tone comes like a punch to the gut near the end of the record, Clics Modernos includes “Nos Siguen Pegando Abajo” (They Keep Beating Us Down), whose lyrics, like those of all great rock-and-roll songs, are as universal as they were specific to a certain place and time.

Miren, lo están golpeando todo el tiempo

Lo vuelven, vuelven a golpear

Nos siguen pegando abajo

Look, they keep hitting us all the time

The hit us again, again

They keep beating us down

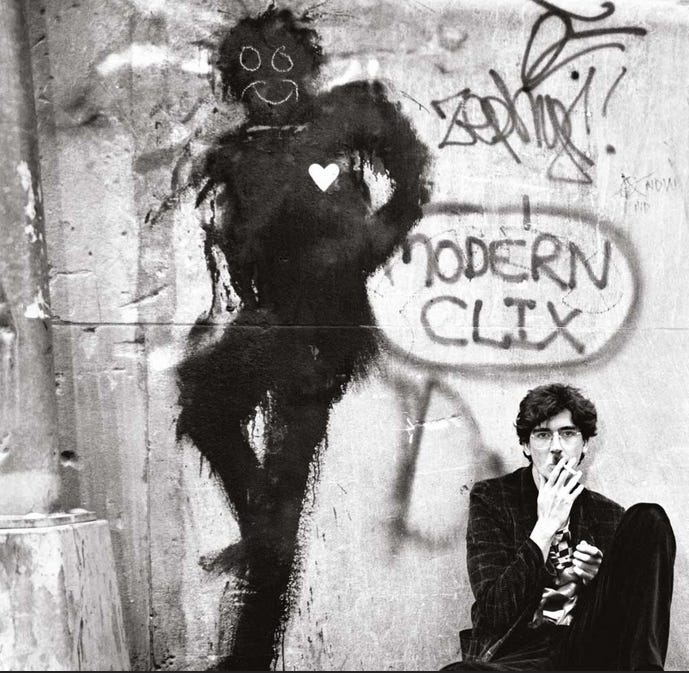

Postscript: In 2023, the spot on Walker Street and Cortlandt where the cover photo for the album was taken was renamed “Charly García Corner.”

This story contains excerpts from previous articles I wrote for Billboard magazine, Universal Music’s website Udiscover Music and for the roots music journal No Depression.

Further reading:

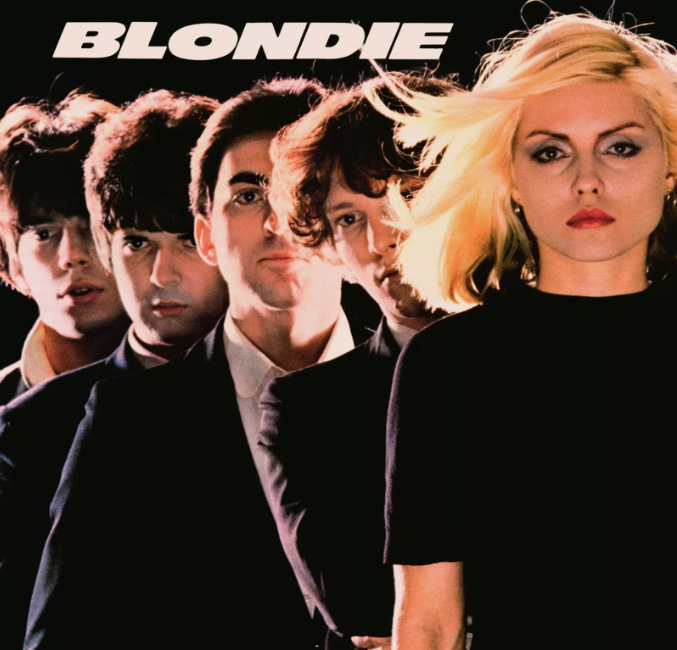

Remembering Clem Burke: The Blondie Drummer on CBGB, Punk, Disco, Cuban percussion, the Ramones...

I’ve been away from the media a bit, so I just read the very sad news of Clem Burke’s death on the NY TImes this afternoon.

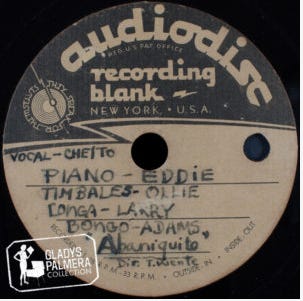

In 1951, Bronx teens Orlando Marín, Joe Quijano and Eddie Palmieri formed The Mamboys

I woke up to the news that salsa and jazz icon Eddie Palmieri died Wednesday (Aug. 6) at the age of 88.

Bobby Marin's New York Groove

“I sang in a group called the Del Chords on my block. We sang at the Apollo theater on amateur night a couple times. We would be rehearsing, usually in hallways in the building to get the echo effect. Then the people would be saying ‘shut up!’ They’d throw us out, so we’d come outside, and our friends would be jamming, banging on cars and trash cans, an…