In 1951, teens from The Bronx named Orlando Marín, Joe Quijano and Eddie Palmieri formed The Mamboys.

An oral history.

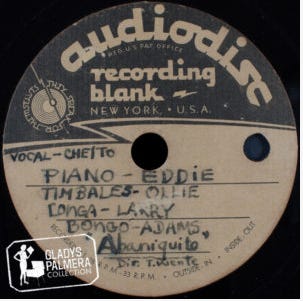

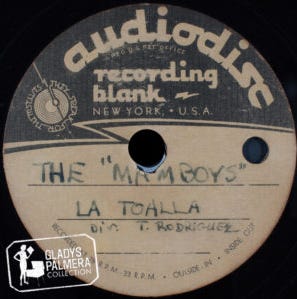

The name The Mamboys is written in black magic marker, and below, the name of the songs: “La Toalla” (“the Towel”), a version of the Tito Rodríguez hit, on one side, and on the other, “Abaniquito,” (“Little Fan”) the song by José Curbelo and Bobby Escoto made famous by Tito Puente. The first names of the musicians make a crowded list in block letters. Orlando Marín, then known as Ollie, Joe Quijano, nicknamed Cheito, and Eddie Palmieri, were 16, 15 and 14 years old when they climbed the stairs to a studio in East Harlem in Manhattan where they could make a record, and just moments after hold it in their hands.

When I interviewed the members of their childhood group, in 2019, they were 84, 83 and 82 years old. Orlando Marín, who was by then known to audiences in New York as “The last mambo king,” passed away four years later. Joe Quijano died in Puerto Rico just a few months after I spoke with him; his music is preserved on his own label, Cesta Records. When Eddie Palmieri turned 88 last December, he posted on Instagram: “I adore all of my lovely fans who’ve expressed an outpouring of support for my health and my 88th birthday.” On July 18, 2024, New York City proclaimed the date Eddie Palmieri Day.

As kids, Marín, Quijano and Palmieri lived on the same street–Kelly Street in The Bronx, where they played stickball, a form of inner-city baseball using a broomstick and a ball made of rubberbands.

The spent their weekdays at PS 52 on the same street, a school now known for producing some of New York’s finest musicians.

Marín, Quijano y Palmieri shared their memories of The Mamboys, a boy band that got together during lunch hours at school and then played at school dances on Fridays, with me during separate phone calls. Their reminiscence reveals how that particular place and particular time spurred the formation of their precocious musical group.

Listen to a soundtrack for this story:

Listen on Qobuz

KELLY STREET AND THE PUERTO RICANS IN THE BRONX

Joe Quijano: We lived on the same block on Kelly Street. Orlando Marín lived at 909, I lived at 985, and the Palmieris lived a little further up the street, in the middle of the block, near Longwood Avenue.

We were 13, 14 y 15. PS 52 was also on Kelly Street between Longwood and Prospect Avenues in The Bronx. Now the school’s famous because so many musicians came out of there, in addition to us: Héctor Rivera, Manny Oquendo, Ray Barretto… a lot of Bronx musicians went to that school.

I arrived in New York in 1941, when I was seven years old. At that time, many of the immigrants from Puerto Rico who came to New York lived in the Manhattan area, at 110th and Fifth Avenues. Because the Puerto Ricans in those days, during World War II, worked in the munitions factories. The Italians lived towards Third Avenue, and they wouldn't let the Boricuas pass that way, on the east side. They would come down on you. It was segregation in those days.

All those places, which were where the Jews had their weddings and the Italians had their functions, were bought by Boricuas, because the Boricuas were the ones who were dancing. In places where there used to be one wedding a month or something like that, when the Boricuas came in, they went out dancing three days a week: Friday, Saturday and Sunday. Joe Quijano

There was a place in The Bronx called the Tropicana. The owners were Cubans, and they were the managers of the famous boxer Kid Gavilan. That lounge was on a third floor behind a big pool that was there. The Tropicana brought a lot of Boricuas to that area. The greats like Benny Moré, Arsenio Rodríguez or Antonio Arcaño had a lot of attraction for the Boricua. People also danced danzones then; singers like Machito, Miguelito Valdés began; many who left Cuba came and played at the Tropicana. With time, all those places, which were where the Jews had their weddings and the Italians had their functions, were bought by Boricuas, because the Boricuas were the ones who were dancing. In places where there used to be one wedding a month or something like that, when the Boricuas came in, they went out dancing three days a week: Friday, Saturday and Sunday, dancing to Cuban music. There in the Bronx was where the rumba got started in New York.

Eddie Palmieri: At that time, the commercial radio stations were playing Machito and Tito Rodríguez music every day. All the bodegas in the neighborhood would turn the radio volume up loud, and while we were playing stickball in the street, we were listening to all the new records that came out.

THE MAMBOYS

Orlando Marín: I’m the one who organized a group, because in 1950 when the mambo came out I loved it; I was dancing every day. I was a poor child, my mother died when I was 10 years old. I had given up music, dancing and singing, but when the mambo came out, I started to sing again and follow the rhythm. And when I heard the timbales, I said, "I want to play timbales." So I got a pair of timbales and decided to form a band. I was 16 years old.

My family bought me the timbales and some cowbells. But I said to myself: for God's sake, I don't know how to play, nobody is going to hire me to play. And I thought: I can't play because I have no experience. So I'll make a band with the neighborhood kids and we'll learn together. I'll make a band with kids like me.

Joe Quijano: We called ourselves the Kelly Street Mamboys.

Orlando Marín: In 1951, I started to organize the musicians. I found a pianist who lived in front of the school. There was someone who played the conga, I got him for the band, and I started to get other musicians. We started rehearsing at PS 52 every week.

Joe Quijano: At lunchtime we could use the piano in the auditorium.

Orlando Marín: I had a piano player, but he left after a few weeks, and I needed another one. I found a 14-year-old boy who lived on Kelly Street. His name was Eddie Palmieri. I went looking for him.

Eddie Palmieri: We were kids.

Orlando Marín: It was Eddie Palmieri who recommended Joe Quijano to me. He lived on the same block as me, on Kelly Street, and we are still very good friends. He was one of my best friends.

Joe Quijano: (Louie) Chiqui Pérez played conga, and there was Larry Chino Acevedo who played a little trumpet.

Orlando Marín: Chiqui Pérez, a very good bongocero who later played with Puente and Rodríguez. And Larry El Chino, who was my main trumpet player.

Joe Quijano: We were rehearsing there, playing the first number, which everybody knew, “El Cumbachero.” The thing was, that was the only number we knew.

Orlando Marín: And then they told me: Look, you're going to have to pay for the hall where they rehearse, or else they'll have to play every Friday for the kids, to get them off the streets, off drugs. So that's what I started doing. Every Friday I had to play at PS 52; otherwise they would charge me for the hall.

Joe Quijano: We started playing a dance at the Hunts Point Palace. We were paid five dollars -one dollar each- and we had to learn more numbers.

Orlando Marín: In those days we copied songs by Tito Puente and Tito Rodríguez, and sometimes by other Cuban groups.

I remember it was there in Harlem because before, when I was younger, I sang, and my brother Charlie accompanied me on the piano. My father, Carlos Manuel Palmieri, had taken my brother and me there to record. Eddie Palmieri

THE FIRST RECORDS

Joe Quijano: We did the recording on 119th Street and Lexington Avenue. There was a walkup and there was a man who had a studio, and while you played, he made a copy of the recording. I kept it for many years, and when I had the opportunity I converted the record to CD.

Orlando Marín: We recorded Tito Rodríguez’s “La Toalla,” and Tito Puente’s “Abaniquito.”

Eddie Palmieri: I remember it was there in Harlem because before, when I was younger, I sang, and my brother Charlie accompanied me on the piano. My father, Carlos Manuel Palmieri, had taken my brother and me there to record.

BOYS TO MEN

Joe Quijano: Since we were 13,14,15 we were polishing our playing, and we were playing more often. After two years, Orlando Marín made an ensemble. Now he had four trumpets, piano, timbales, conga, bongo, two singers, and I was one of them...We were already 16,17,18 years old. The Conjunto Orlando Marín sounded beastly, a style like Roberto Faz in Cuba.

Orlando Marín: In those days I was the youngest bandleader. In 1953, I got a job playing at the Palladium Ballroom, playing on the same stage with Puente and Rodríguez. I played at all the clubs in the Bronx, and at the Taft Hotel in Manhattan every Saturday and Sunday.

In 1958 I was drafted into the army. I was against the war, but I had to leave. It broke my heart to leave my musicians.

Joe Quijano: Then Eddie Palmieri took over the band.

Eddie Palmieri: And from there I moved on. My brother told me: If you want to be a musician you have to play with professional orchestras. He recommended me to all the bands I was in. The first one was Johnny Segui's orchestra, in 1955. Then I went with Vicentico Valdés -when my brother played with Tito Puente, he was the singer-. And then he made his own conjunto. I joined the band in 1956. And then my brother recommended me to Tito Rodríguez and I was with Tito from 1958 to 1960. And then I formed my own band.

Joe Quijano: Eddie went to work with the Conjunto Segui, and I stayed with the conjunto. But I changed the combination: I put two trumpets and the flute.

Orlando Marín: Later I started recording with Alegre Records: [the album] Se Te Quemó la Casa was a hit. Throughout my career, I have always given more opportunities to young musicians, because that's how I learned.

____

The Mamboys’ demo is part of the Gladys Palmera Collection of Afro-Cuban and Latin American music in El Escorial, Spain. The original version of this story first appeared in Spanish on the Gladys Palmera website.

For more New York Latin stories, please read my interview with Bobby Marín.