This New Exhibition Tells the Story of the Central Park Rumba

An interview with photographer Juan Caballero

Over the years of documenting the Central Park rumba with his camera, Juan Caballero has often heard some of the regulars call it by a different name.

“They call it the clinic,” he says. “It’s where people go to get cured.”

The therapeutic sound of the wooden clave sticks and congas, strains of collective singing in Afro-Cuban dialects and laughter have called people of various background and intention to the shores of the lake in the park for some 60 years. More than just a super-charged drum circle, the Central Park rumba has been a cultural happening and an essential social phenomenon.

“The rumba is where people go to spend some time and disconnect from their problems,” says Caballero, who grew up in Cuba and is talking to me from his home in New York City. “It’s where people go to have fun, find some space, to dance and sing or excessively participate in the present. That’s the essence of the rumba.

“One day I heard someone say that when you go to a rumba the differences between you and other people disappear,” he adds. “It’s true. That’s what I try to do in my pictures; I include everyone who’s there.”

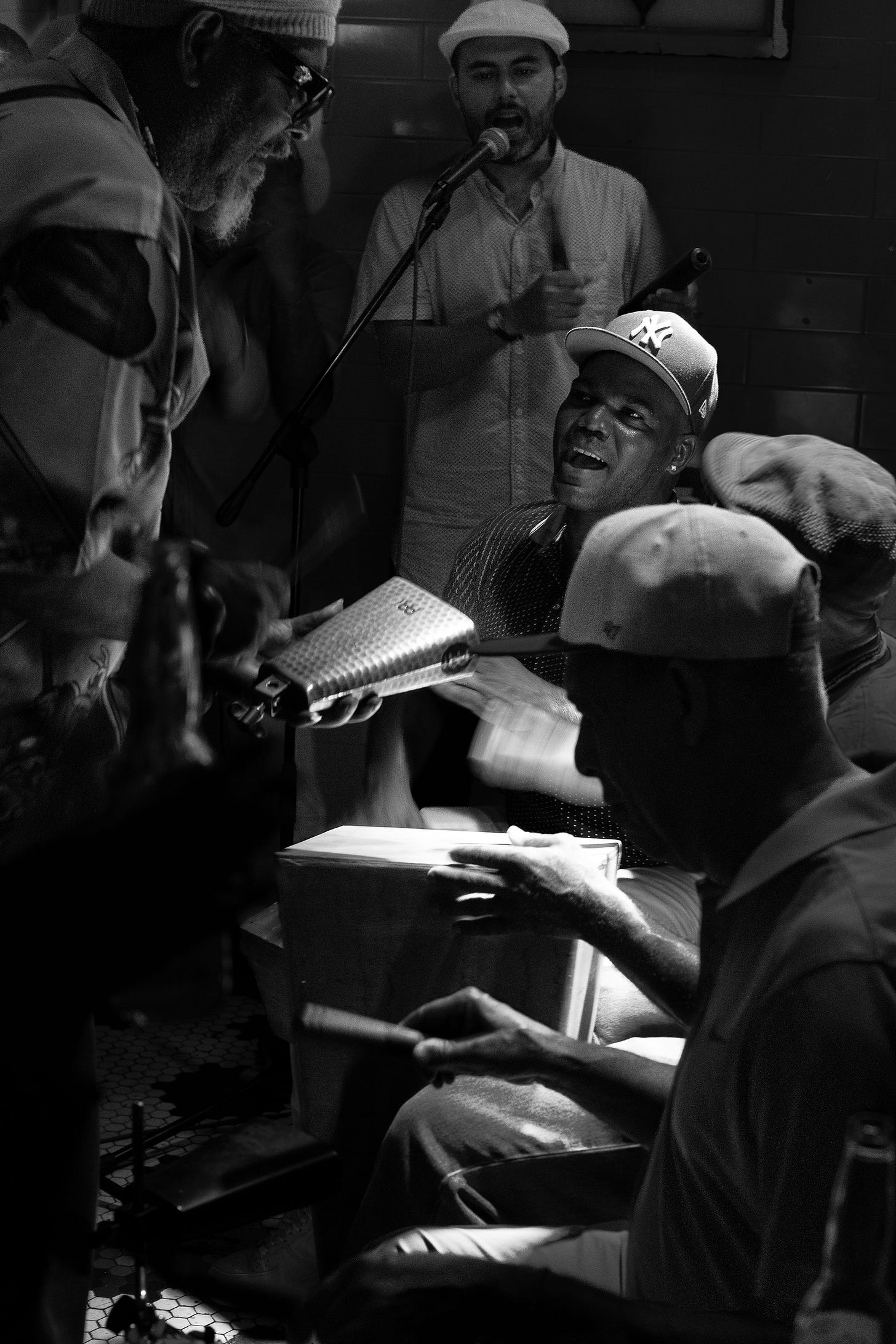

Starting this Thursday, December 19, Caballero’s majestic black-and-white photographs of musicians, free spirits and people who, like the roots of the Cuban music of ritual that they are playing, are on the margins of the mainstream, will be exhibited at City Lore in downtown Manhattan. Rumba Entre Puertas will document and interpret the Cuban rumba tradition as performed in New York City in an exhibition about “multigenerational community resilience” and the evolution of the Cuban rumba, from sacred to secular, in the diaspora.

And attention: A series of musical performances starts with the opening reception/holiday party on Thursday, when the Cuban conguero Román Díaz, a central figure at the Central Park gatherings who has schooled others in the rumba musical tradition, will perform. Díaz will also lead musicians on an album to be recorded next weekend. “On the record you´ll hear all of the different contributions to the music,” says Caballero. “It’s going to sound like something new – that’s the New York rumba.”

Caballero has photographed Cuban religious ceremonies and percussive social gatherings in Havana and Miami, around New York City – for almost 25 years in Central Park.

The photographer notes the weekly improvisational event’s origins: “It was a mix of people from different countries, professionals or amateurs who had been going since the 1960s, who were Puerto Ricans, Americans, some Black Americans, Jews. The typical New York mix, a multicultural community. “

In 1980, the rumba’s make-up was altered by the arrival in the city of black Cubans who came via the Mariel Boatlift, who upped the authenticity of the rumba played in the park.

“A lot of them had never played rumba, but they did live in the solares, in the poor places, the tenements of Havana,” Caballero explains. “They were born into that, they lived that. Maybe they hadn’t played the music, but they could hear it from inside their houses, in their neighborhoods. So it was in their blood, in their genes, even though they weren’t rumberos. So when they got here, the rumba was a way for them to reclaim what they had lost and reconnect to their past, and with everything that they no longer had.”

Caballero, who is now 58 years old, told me about his own relationship with the rumba and other traditional Cuban music. It’s a story of teenage rebellion.

“Honestly, what happened in Cuba was what happens when you live one an island, and also when you’ve lived under a totalitarian system your whole life. They told us that American music was the music of the enemy, that there would be what they called ideological penetration if you listened to music from the United States. So of course, that made us love American music.

“Growing up in Cuba, I lived surrounded by the religious Afro-Cuban music. My neighbors, the parents of my friends, were Santeros, they had religious celebrations for the saints in their houses, but I wasn’t really interested.”

In 1993, Caballero left Cuba for Buenos Aires, where he studied photography. Four years later he returned to Havana, where, through his camera, “I started to see Cuba from the outside, with different eyes, and I started to value its culture, things like the rumba.”

Through a friend, he started to hang out with rumba percussionists, members of the sacred brotherhood that performed at religious ceremonies, and he got to know the members of the prestigious rumba groups Yoruba Andabo and Clave y Guacuancó. He started going to the “fiestas de santo,” where the rhythms saluting the different orishas - the Afro-Cuban deities - are played in people’s homes, and to the group’s rehearsals and parties. And he started taking his camera to the sacred and festive gatherings.

In the year 2000, Caballero emigrated to the United States. He later moved to New York City. It was in 2010 that a friend took him one summer Sunday to a rumba in Central Park, where the diversity of the participants expanded his definition of the word rumba.

“So that same year, I started to go every Sunday with my kit, camera, flashes, everything I used then in those analogue days. I started taking pictures and got to know the regulars and became friends with them. I have a lot of portraits of people who are no longer alive, who had come in the 80s with Mariel and already older then. From 2010 until today, until last summer I’ve never stopped going to the rumba in the park.

“The rumba here in New York was different from the rumba in Cuba,” Caballero observes. “There is a concept in Cuba that if you don't know how it’s done, if you don’t know the rules as they say, you don't get involved. You don’t interrupt.

“In New York the rumba is profane, the rumba is open to everyone, although many saints are named because it is [musically] linked to the religion. If someone arrives who knows how to sing, that person will just step in and start singing. Then there are others who get drunk and interrupt the rumba. The rumba in Central Park has everything. Sometimes the music is even not good, but you always have fun, because it is these things, the characters who come there, that make it what it is.

“It’s spontaneous and open, the way an authentic rumba is. Everyone who can participate, whoever can sing and play.

“I’m not a musician, I don’t know how to sing,” he adds. “But I join in and sing chorus, because there’s a saying that goes sin coro no hay rumba. If no one sings, the rumba doesn’t exist. So when I’m taking photos, I try to sing along too. I participate. I’m always an observer. I’m a person who you’re never going to see stand in front of someone while they’re playing or blocking the view. I don’t like to call attention to myself. I’m always standing in a corner, on the side, and if I go up front it’s just to get a photo and then I’ll slide away. I’m not there to be in the center of the action. The important thing for me is to capture the natural character of the rumba, that spontaneity of the rumba.”

Caballero has documented rumba gatherings in other places in New York City, like the restaurant Mi Salsa Kitchen on the Lower East Side, that closed in 2023. He also spent several years living in Miami, where he participated in the very active world of Saint’s Day celebration and initiation ceremonies. During that time, he made visits to New York and the Central Park rumba. He moved back to New York City in 2018. The Rumba Entre Puertas features Caballero’s black-and-white photography and focuses mainly on the Central Park rumbas, with some photographs from other locations. But he is also working on a book that will create a more complete record of his work documenting rumba in Cuba, Miami and New York over the years.

Caballero’s work and the exhibition at City Lore underscore the social significance of the Sunday rumbas in Central Park, particularly for a sector of the Latino immigrant population.

“The rumba in Central Park has been a constant, it’s existed Sunday after Sunday for 60 years,” Caballero says. The people who go there are the protagonists of the rumba, whether they’re musicians or not. The señoras who bring food and sell it, the friend who brings the beer. It’s been a way for people to survive in this country. This is a totally different culture for those people, who don’t even speak English. More than being about just music. it’s also told me a lot about the history of my country after 1959.”

As the rumba has evolved over the years, it has also been threatened by changes in the city. In the 1990s, then-mayor Rudolf Giuliani tried the put a stop to the weekend gatherings, citing noise complaints from residents of neighboring buildings and laws about unauthorized social gatherings. Drums were confiscated, but the rumbas continued in some form, even with coolers as congas.

Today, Caballero explains, the police still walk by scanning for open containers and social disorder.

“The musicians just wait for police to leave,” he says. “then they start playing again.

“The rumba is ancient music that is ageless,” he adds. “It will always sound modern and in step with its time. The rumba never dies.”

Thank you. I especially like this quote: “It was a mix of people from different countries, professionals or amateurs who had been going since the 1960s, who were Puerto Ricans, Americans, some Black Americans, Jews. The typical New York mix, a multicultural community. “

Love it!