Cuba on Record: The Book, Substack Edition

The story of Panart, the pioneering Havana label that captured Cuban music and took it to the world

A central feature of my Substack is the story of Panart Records, the first and forgotten independent Cuban record company. I am sharing chapters of my serialized book, in a special music-enhanced Substack edition, also called Cuba on Record for paid subscribers. Each installment will be accompanied by a playlist that serves as the chapter soundtrack, highlights from my annotated discography of Panart recordings, plus photos and videos and other historic wonders I’ve come across in my research about Panart, Cuban musicians and the evolution of the musical relationship between Cuban and the U.S.

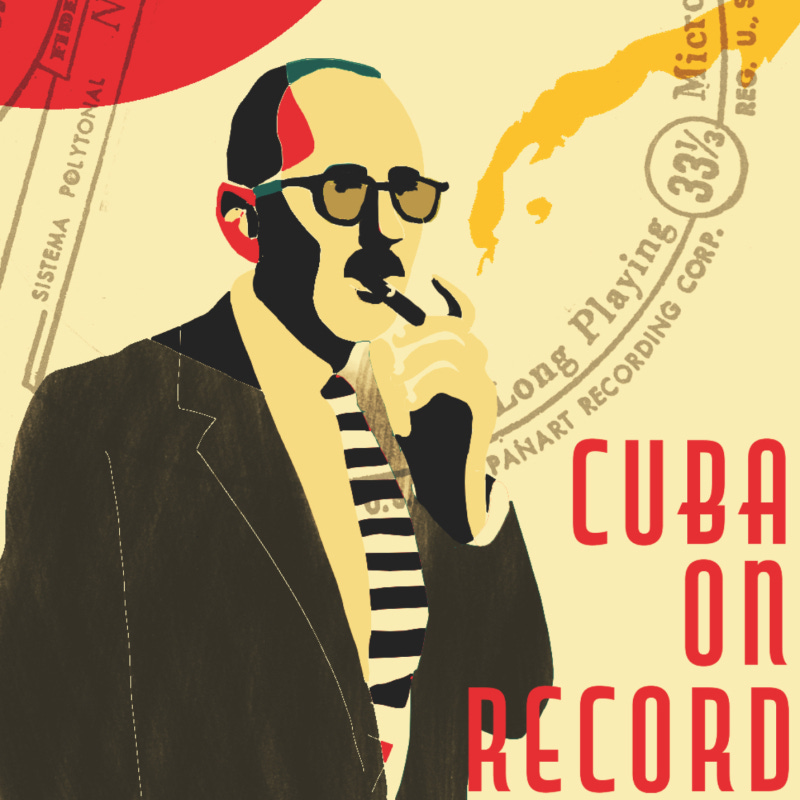

Panart Records captured a euphoric era in entertainment and brought Cuban music to the world. In 1943, Panart’s cigar-wielding founder, Ramón Sabat, converted a colonial house in downtown Havana into a recording studio, setting the scene for the creation of pioneering sides including the Afro-Cuban chants that were Celia Cruz’s surprising first singles, the first cha-cha-chá, Mambo King Perez Prado’s early dance numbers, Buena Vista Social Club singer Compay Segundo’s solo debut, and Nat King Cole’s first Spanish-language album.

“Panart led the way to the vigorous flourishing and widespread dissemination of Cuban music. It opened wide its recording studio to established artists and undiscovered talent; gave voice to Cuban composers; revived and recorded the traditional and introduced new and innovative forms such as the mambo, the cha-cha-chás and the jam sessions.” Julia Sabat

Sabat was a visionary entrepreneur and innovative engineer, a society geek who wore a tuxedo as casually as pajamas, but whose nightcap of choice was Coca-Cola. The first Cuban record company that would challenge the stronghold of RCA Victor on the island, Panart encompassed the label, the island’s first record factory and the recording studio. Sabat’s goal was to both create a thriving market for domestic recorded music in Cuba and take Cuban music to the world through partnerships with international labels, both groundbreaking ideas in those early years of the recording industry. Together with Julia Riera Sabat, Ramón’s wife and the Vice President of the company, his brother Galo and other family members, and the pioneering Panart employees in the studio, factory and offices in Havana, and later New York, Sabat succeeded at both.

“Panart had all the best artists of the era because Ramón Sabat gave everyone an opportunity.” Pianist Bebo Valdés

His seemingly impossible dream to record every kind of Cuban music paid off by the 1950s, when Panart was annually selling over a million records, pressed in the island’s first record factory and played on Havana’s 10,000 jukeboxes. The label captured Cuban music’s golden age, whose rhythms were the soundtrack to post-war glamour and political turmoil, when new tourist-packed planes and aggressive U.S. businesses collided with mafia-run casinos and rebel bombs. Then, one morning in 1961, Panart disappeared.

“Everyone knew about Panart. It had prestige.” Cuban singer Olga Chorens

The immortal Latin songs the label brought to the world have continuously spawned new and diverse cover versions through the decades and influenced music styles from jazz and rock to, of course, salsa. I’ll be creating a portrait in words and music of a time when Cuban and U.S. musicians came together through their music and how the legacy of that period in the mid 20th Century can be heard in recordings made in Cuba and the United States over the last 80 years, until today. The Panart studio would continue as the center of all Cuban music production in Havana even decades after the label’s abrupt demise, as the studio for the Cuban State-owned label Egrem, founded on the premise that a record label should value culture over commerce. In more recent years, the former Panart studio became a destination studio for international producers, although its glorious past as the motor of Cuban music recording is unknown to many of them.

I’ll tell the story of the spectacular rise and sudden fall of Panart through interviews with Cuba’s greatest musicians, members of the Sabat family, historical testimonies and musicological research. As people familiar with my work probably know, I’ve been investigating the story of Panart and its musical and social context for years, a task that’s taken on new relevance now that music from the label’s catalogue is now available on streaming platforms. But like many other musical treasures to be stumbled upon in the cacophonous jumble of our digital age, they can remain difficult to find and often uncredited, and the origins of the songs and identities of many of the recordings and the musicians who made them are murky. My goal is to restore Panart’s deserved place alongside legendary labels like Chess Records, Motown, Fania and Fuentes, revealing the origin stories of classic songs that have since broken through ideological barriers, and tracing Panart’s influence on the music of today.

Why am I publishing on Substack?

I’m always game to try something new, for both curiosity and necessity’s sake. As a journalist facing the current changes and challenges of my profession, I’ve decided to publish on Substack. Some of my reasons why have been laid out by Ted Gioia on his own essential and inspirational Substack.

Among my own reasons are the freedom to write and publish at my own pace, and to enhance the book with music that readers can listen to as they read and save for their own libraries, as well as vintage images and videos that bring the period alive.

Fundamentally, paid subscriptions will contribute to supporting me while writing. I’ll retain publishing and translation rights, and importantly, I’ll be able to receive feedback from readers that can contribute to a revised edition that I may publish as a physical book (ideally in English and Spanish versions) in the future.

I am in awe