Celia Cruz and Tito Puente's Own Summer of Love

As “American Tribal Love Rock Musical” Hair exposed, this was the dawn of a new era. And the times were changing for Latin music.

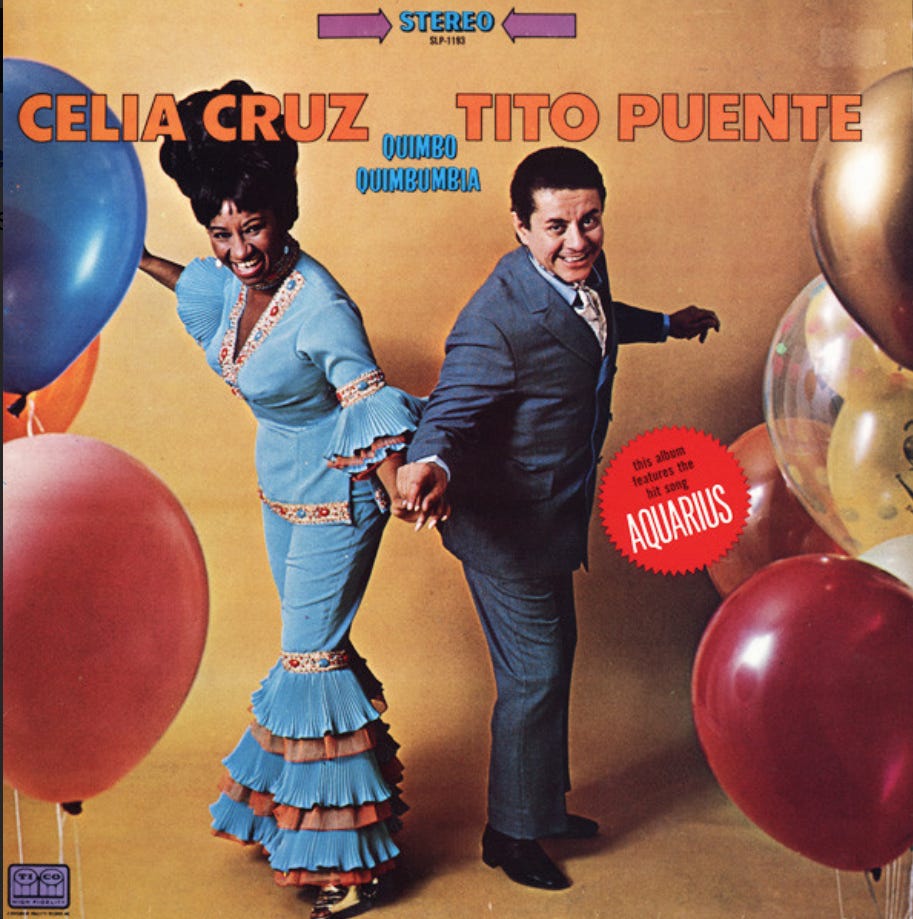

In this second installment of my CELIA CRUZ 100 YEARS/100 SONGS series in celebration of Celia’s centennial, I tell the story of Celia and Tito Puente’s version of “Aquarius” from the musical Hair, and the 1969 album Quimbo Quimbumbia. On October 21, 2025, a cry of “Azucar” will be heard around the world, marking 100 years since Celia’s birth.

Tito Puente and Celia Cruz recorded their Spanish version of “Age of Aquarius/Let the Sun Shine In” in May 1969, when that mash-up of two numbers from the Broadway musical Hair by the 5th Dimension was the number one song on the Billboard chart, on its way to winning the Grammy for Record of the Year. Puente’s arrangement added congas, timbales and the punch of Latin big band horns to the groove of the hippie culture-inspired psychedelic pop spiritual. The track starts off dance-floor frenetic, leveling out as Cruz’s echoing vocals call out “Acuario” to the universe, then brings it in for what feels like the tight drum circle of an Afro-Cuban ceremony, with the singer’s voice spiraling into a soul-shaking chant:

“La la la la

Que brille el sol

El sol que alumbra” (“Let the sun shine, the sun that sheds light.”)

In a televised performance of “Aquarius,” Celia appears in the snug tropi-pop pant suit with ruffled bell bottoms and sleeves that she wears on the cover of Quimbo Quimbumbia. Her high hairdo holds steady as she go-gos and rumbas alone on a round stage in silver shoes, her hoop earrings shaking to the beat. It was not what audiences may have expected from a Cuban nightclub star then best known for wearing sequined cocktail gowns as she sang with a tropical big band.

“Our adaption of that song was a hit around the world” Celia later declared in her autobiography, Celia: My Life, written with journalist Ana Cristina Reymundo. It was a welcome success. At the time, Puente, iconic bandleader of New York’s mambo scene, and Cruz, whose fan base had grown beyond Cuba to throughout Latin America, were so well known that they could release an album using just their first names. But, as Hair, the “American Tribal Love Rock Musical,” so frankly exposed, this was the dawn of a new era. And the times were changing for Latin music.

“Young people, the major target audience for the music industry, began to turn their back on our music,” Cruz later recalled. “…The late 1960s and throughout the 1970s was the age of rock and disco, and as a result, my people’s music was barely played. Many believed that Cuban music was something of the past, and that it belonged only in the homes of Cuban exiles and at dances for older people. In other words, Cuban music just wasn’t hip.”

“…They saw it as old fashioned,” she lamented. “As a result, we went through a couple of slow years.”

Nuyorican Tito Puente had always been a trendsetter, able to translate the spirit of the day into music, and also to spot talent: in 1965, three years after Cruz had landed in New York from Cuba for good, he orchestrated her signing with Tico Records. Quimbo Quimbumbia was the second album the artists made together on the label.

“Tito Puente was one of the first… to have a female singer be the front of an orchestra,” Tito Puente Jr. explained in a 2023 BBC audio documentary about the pioneering bandleader. “But not only that, my father really went and pushed it into the faces of the American public by not only having a female but having an Afro-Cuban black woman fronting an orchestra. And that was really a shock to everybody at that time, in the 1960s.”

The gorgeous and groovy Celia Cruz on Spanish television in 1970:

With their version of “Aquarius,” Puente and Cruz quickly capitalized on the success of Hair in New York and beyond: in 1969, the musical had its Spanish-language premiere (and was raided by police) in Mexico, and it was soon shocking audiences in some South American countries. As the opening track of Quimbo Quimbumbia, the unexpected version of the then ubiquitous song announced that neither Tito and Celia nor Latin music were going to fall behind the times.

Hair premiered on Broadway in 1968 after workshopping at Joseph Papp’s downtown Public Theater and then, unconventionally, at a nightclub, The Cheetah Club. In a review of the Broadway production in The New York Times, critic Clive Barnes cited its references to drugs and homosexuality, its instantly famous nude climax, its racially diverse cast and “attitudes of protest and alienation.” The show rocked the conventions of the New York theater world and created a stage for the clash of generations and a search for identity that, against the backdrop of the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement, and, in New York City, a steep rise in the Puerto Rican population, was calling into question what it meant to be American.

Tito and Celia’s version of “Aquarius” could be seen as a show of Latino pride, an answer to those who questioned their cool, and the potential of their appeal to any audience. Other artists in New York were singing in English, cooking up the boogaloo, a crossover style that fused R&B with Latin rhythms, with English lyrics. But Quimbo Quimbumbia is entirely in Spanish, with a repertoire astutely selected and produced by Puente to have success with international audiences, beyond the New York barrio.

The songs on the album include “Génesis,” a ballad that had won first prize at the inaugural International Latin Song Festival in Mexico City, where it was performed by the popular young Puerto Rican singer Lucecita Benítez, just two months before it was recorded by Puente and Cruz.

“Corazón Contento” covers a 1968 hit for the Spanish pop pioneer Marisol, who brought rock-and-roll attitude and flamenco airs to a mass audience in the time of Franco’s dictatorship.

On “La Danza de la Chiva,” Celia stretches her vocal muscles to a frisky merengue beat. A guaracha that winks to cumbia, “Quimbo Quimbumbia” was written by José Carbó Menéndez, the mid-Century Cuban composer who supplied Celia and Tito with the popular song “Cao Cao Mani Picao.”

More nostalgic, “Mi Querida Borinquen” is an emotional ode to Puerto Rico; and the jaunty mambo “En El Cafetal” covers a song previously recorded by Daniel Santos, the famed singer who, like, Celia, had performed with the Cuban orchestra La Sonora Matancera.

The powerful “Yo Soy la Voz,” is a more bittersweet look back. Declaring herself “the voice of the Cuba of yesteryear” in the song, Cruz references her own exile from Cuba, taking a dig at Castro’s Revolution by declaring “I am free as the wind,” and admonishing that “the moment will come when music that left Cuba will return.” She pounds that political message home with “Yo Regresaré,” a cha cha chá with the country flavor of “Guantanamera” that includes her spoken message of encouragement for Cuban exiles: “No podemos perder la esperanza…volveremos a nuestra hermosa Cuba” (“We can’t lose hope…we will return to our Beautiful Cuba.”)

Cruz, who died in 2003, never went back to Havana. She would gain immortality as the queen of salsa, the music that some say was officially born at a wild jam session by the Fania All Stars on a night in 1971, at The Cheetah, the same New York club where the musical Hair had its tryout. Two years later, Celia would sign with the Fania label, igniting her global superstardom, which remains such that in 2024, the U.S. Mint would imprint the image of Cruz, the Afro-Cuban singer who Puente boldly put at the front of the band, on a quarter.

Puente rode the ebb and flow of the waves of Latin dance music’s popularity until his death in 2000. In 1970, Carlos Santana recorded his song “Oye Como Va,” increasing Puente’s income exponentially for decades and consecrating his name in the halls of rock; that song, in a sense, brought his music full circle, back to the young Latinos who had once passed it by. And by now generations more. Listening to these songs, the evergreen appeal of the music rooted in Cuban rhythms is undeniable. And it was obvious to Celia Cruz and Tito Puente all along.

“Hispanic youth felt compelled to dance to pop music in American clubs because it was fashionable,” Cruz reflected in her autobiography. “It may have been good music, but it just wasn’t theirs. It’s like dancing in borrowed shoes: no matter how nice they are, they still just don’t fit.

“It may be true that everything has its time and place,” she added. “But quality never goes out of style.”

Listen to “Aquarius” and other songs from the album Quimbo Quimbumbia on my Celia Cruz - 100 Years/100 Songs playlist, celebrating Celia’s centennial. I’ll be adding to it regularly through October 21, 2025

On Spotify:

On Qobuz:

Thanks Aurora - it's Interesting to read your own personal experience of the disconnect with the new generation and identity crisis that Celia was experiencing at the time of this recording. Yes as you point out, the autobiography is definitely a flawed book but illuminating just the same for the first person accounts from Celia (whether or not you agree with her version of events)..

Pancho Cristal aka Morris Perlman - another fascinating personaje - would love to hear about any personal encounters you had with him if you knew him personally!

I had the great Pleasure to see and hear both together on a great Night at the Montreux Jazzfestival.

It was a Time Jazz was still played in Montreux, great Brasilien Pop, Salsa, Latin Jazz and CuBop as well as The Tango Nuevo of Astor Piazolla and Country Rock mit Carlene Carter, Dave Edmunds and Nick Lowe. Tito Puente and Celia Cruz! I just started to dig deeper into this Music here they were and I was torn in.

Lucky me!