Harold Courlander may be best remembered as the man who sued Roots author Alex Haley for plagerizing his novel The African (Courlander won a settlement.) It should be best remembered that Courlander was a renowned African and Caribbean specialist, an anthropologist who was a collector of folk tales and songs, and author who left a legacy of over 30 books. (He died in 1996, at age 82.)

In 1940, he traveled to Cuba on “a field trip sponsored by the American Council of Learned Societies, in cooperation with Columbia University’s Archive of Primitive Music,” as described by the Folkways Records booklet accompanying the album of four 78s that made up Cult Music of Cuba. From various documentation I’ve found, the set seems to have first released in 1949. It’s now shown up on Spotify; some copies can be out there on Ebay. It’s also available for downloading on the Smithsonian Folkways site.

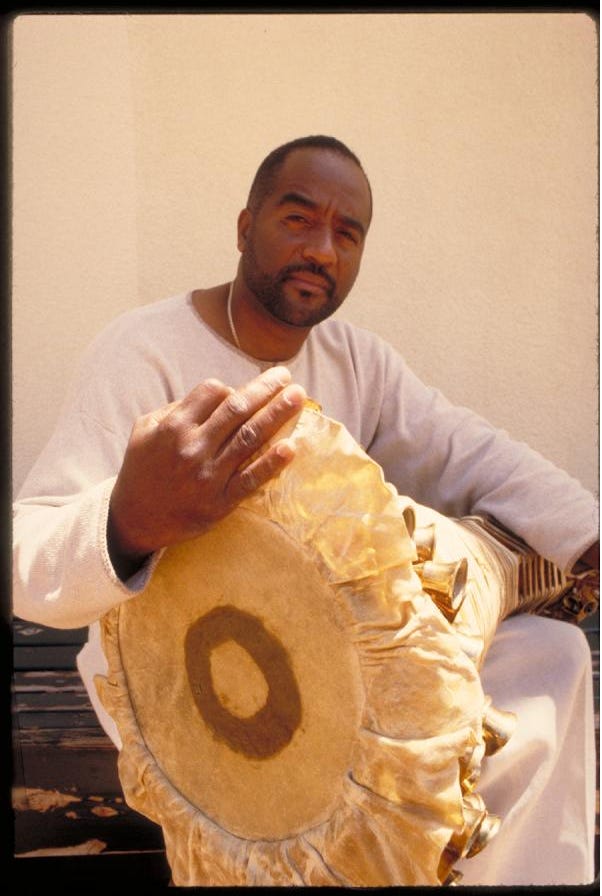

The album features the ceremonial rhythms that call to life the Orishas - the Afro-Cuban dieties that are syncretically paired with Catholic saints. Particularly fierce among them is Changó (Santa Barbara), god of lightening and thunder, but also of drumming, whose feast day is December 4. Changó was an African king in his long-ago residence on Earth, and is a favorite god among worshipers of the religion commonly called Santería. He’s a seductive avenger of evil, and acknowledged as the owner of the batá drums, which were brought by West African slaves to Cuba around 1800.

"It's like the British with their royalty," the Cuban batá maker Ezequiel Torres, a member of the sacred brotherhood of Afro-Cuban drummers, explained to me when I spent time with him for a profile I once wrote about him for the Miami New Times. "Everyone there is obsessed with someone, like Diana -- it's Diana this and Diana that. With us it's Changó and Changó and Changó forever."

In his album text, Courlander noted that the album’s “Song to Changó” (track 5) “belongs to the cycle of invocations which constitute a service, and appears to be sung to Changó, the Orisha of lightning and thunder.”

Recommended tracks for percussionists and rhythm enthusiasts: Tracks 7 “Djuka Drums” and 8: “Lucumi Drums,” and my favorite, the “Lucumi Song” (two male voices, drum rattle); track two.

Here is Courlander’s introduction to Cult Music of Cuba, which gives some interesting perspective about the evolution of Afro-Cuban rhythms in popular music, both in Cuba and the United States, throughout the Twentieth Century:

The folk music of Cuba is generally unknown outside of that country. For most of us the term "Afro-Cuban" evokes thoughts of the Conga, the Rhumba, and the Son. Folk music they may be, but with a thick overlay of sophistication and invention; yet in the main they are not “Afro-Cuban,” any more than boogie-woogie is"Afro-American." Such forms represent a considerable hybridization, and in particular instances it would be extremely difficult to find substantial African elements. Among the Guahiros [guajiros], or white peasant farmers, one could until fairly recently, at least, still hear fragments of very old Iberian music that has little in common with the popular city music. Likewise, among their Negro neighbors one could hear true Afro-Cuban, even pure African, music.

For years there has been a controversy in Cuban musical circles as to the origins of the national musical idiom. From a social point of view the final issue of that controversy is not important. But it is a matter of great interest that there really is such a thing as Afro-Cuban music, and this album presents some of its aspects…

The African slave trade continued in Cuba well into the 19th century. Until only a few decades ago there were some among the older generation whose parents actually were born in Africa, and a few aged people in the country who claimed to have been born in Africa. African traditions have survived strongly, in some respects, to this day. Music and dancing of the African variety have persisted in the cabildos, or societies, organized by the Afro-Cubans.

A great many of these societies have a religious basis, while others are survivals ofsecret organizations which existed pre-viously on the African continent. Among the more important African cults existing in Cuba are the Lucumí, the Arara, the Abakwa and the Kimbisa.

In the Lucumí group survive religious beliefs of the Yoruba people who came from the region of West Africa that lies between the Niger River and the Nigeria-Togolandborder. As with the AfricanYoruba, the Lucumí have a pantheon of spirit-gods or Orisha, most of whom are common to both areas. They include Legua (or Etcho) [or Elegguá], guardian of the crossroads; Ogún, god of the mountains; Otchosi, the hunter god; Obatalá, god of iron and war; Changó, deity of storm and lightning; Orula, the curer; Otchun (or Panchagara) [Oshún], the river deity; Yemayá (or Yalode), god of the sea; and many others.

Lucumí music is mainly devoted to supplication and praise of these supernatural beings. The musical instruments used by the Lucumí are drums, large calabash rattles with external bead strikers, and various kinds of bells.

Very insightful read!

LOve this!!!